The Systems Change for Sustainable Tech is a 3-part co-creation series that invites everyone who is interested to use systems thinking to build a sustainable tech future. Together, we will envision a sustainable future for technology, map our current situation using systems maps (causal loop diagrams), identify key leverage points for impactful change, design effective interventions, and create action plans to bridge the gap between our vision and today’s reality. This article recaps the second part of the “Systems Change for Sustainable Tech” series. Systems changemakers from around the world gathered to map the current reality of unsustainable tech; understanding the systemic causes by shifting attention from events to structures and mental models.

To join the third session, Designing fundamental solutions, RSVP on Luma.

On Thursday, June 5th, a community of systems change makers gathered for the second installment of our series, Systems Change for Sustainable Tech. We began by reaffirming the program’s vision: to unlock pathways for social and systemic change through inquiry, empathy, and genuine connection.

Getting to know each other

The audience was diverse, representing perspectives from across the globe, particularly from the US, Canada, Europe, and India. New changemakers who joined us brought diverse perspectives from their respective geographical areas.

Understanding complexity

Complicated systems, like an analog watch with its intricate gears and mechanisms, can be dissected and understood. They produce predictable outcomes despite their initial appearance of complexity. In contrast, complex systems, such as a rugby match, are characterized by a multitude of interconnected relationships and inherent unpredictability.

Through a collaborative exercise, participants categorized various scenarios as either complex or complicated, recognizing that the line between the two can be surprisingly subtle, and that systems can readily shift from one state to the other. This understanding served as a powerful foundation for the tools that we would explore next.

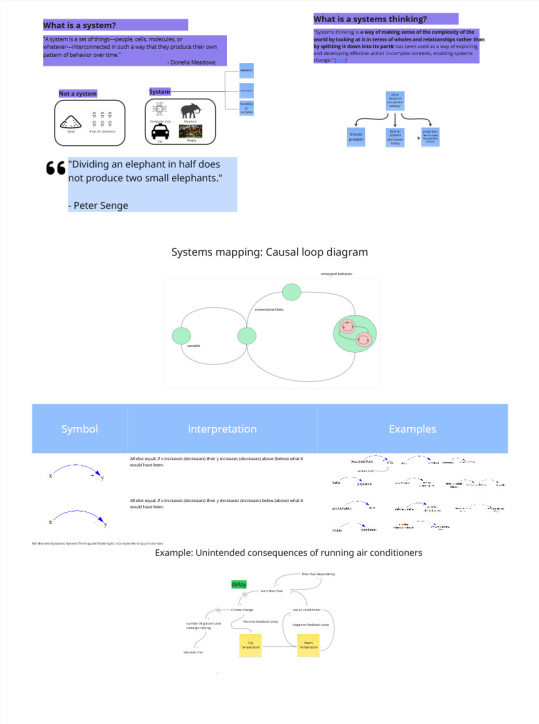

Embracing systems thinking: A framework for understanding complexity

Acknowledging the need for tools to navigate this complexity, we turned to systems thinking. For this workshop, we adopted Donella Meadows’ definition of a system: “A system is a set of things–people, cells, molecules, or whatever–interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time.”

We used Wikipedia’s definition of systems thinking as “a way of making sense of the complexity of the world by looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships rather than by splitting it down into its parts. It has been used as a way of exploring and developing effective action in complex contexts, enabling systems change.” [wiki]

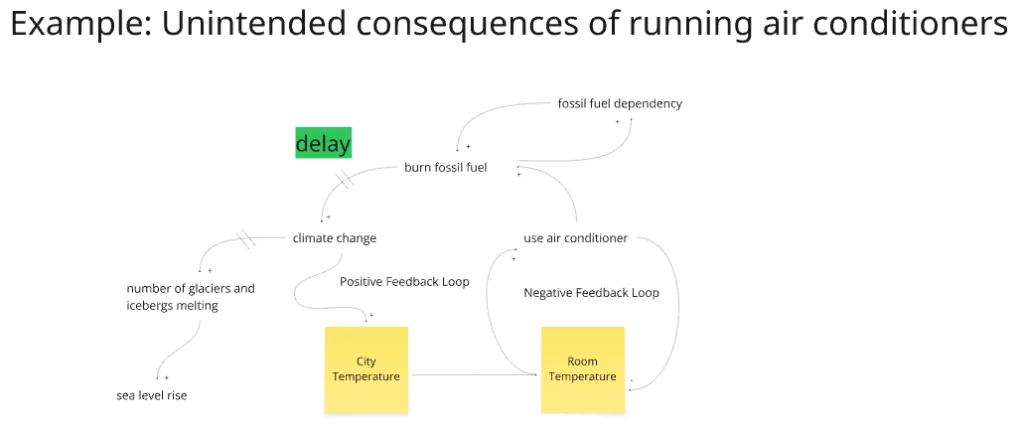

It is important to apply systems thinking to chronic, familiar problems, those that have resisted conventional solutions. We unpacked systems mapping and the core components of causal loop diagrams: variables, connections (positive and negative polarity), delays, and the concept of emergent behavior arising from interconnectedness. We established that any variable can itself be a system, containing its own layers of interconnected variables.

We then explored a practical example of feedback loops, a discussion of the unintended consequences of air conditioning on climate change. This illustrated the dynamics of both negative and positive feedback loops, as rising city temperatures lead to increased AC usage, resulting in the burning of fossil fuels, contributing to climate change, and further exacerbating rising temperatures.

This exercise underscored the power of systems thinking to reveal hidden dynamics and unintended consequences, equipping participants with a vital tool for tackling the systemic challenges of unsustainable tech.

Telling systems stories: Shifting perspective

Understanding complexity is fundamentally about crafting systems stories. To do so effectively requires two critical shifts in perspective:

- From parts to whole: Recognizing that isolated variables don’t tell the full story, it’s the interconnectedness that matters.

- From events to systems: Moving beyond reacting to day to day events, and focusing on the underlying structures that drive them.

Addressing chronic problems demands seeing the whole system, not just its individual parts, and paying close attention to the interplay between variables and the emergent behavior that arises from these connections.

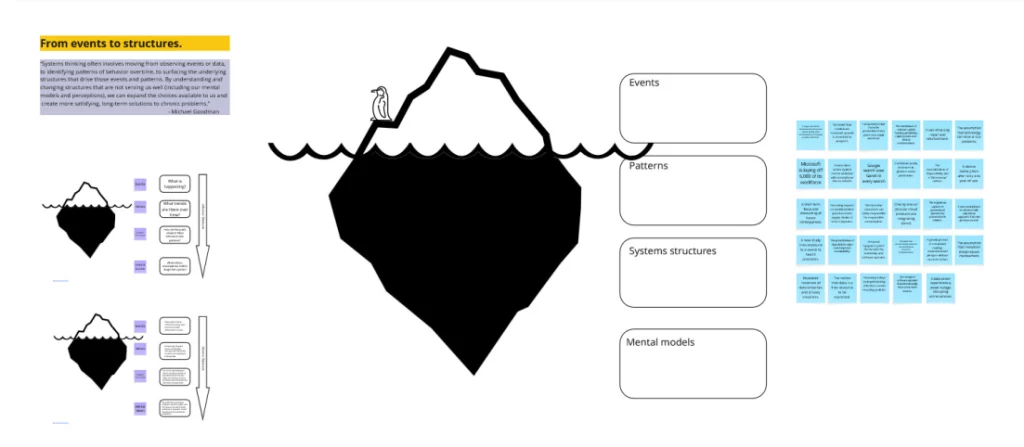

We looked at the Iceberg Model to facilitate this shift in perspective. The Iceberg Model has four layers: events, which are the only visible layer, reveal what is happening; patterns reveal trends over time; systemic structures unveil how parts are related and influence those patterns; and mental models expose the values, assumptions, and beliefs that shape the entire system. Every complex event has a corresponding story that can be communicated through the lens of the Iceberg Model. Participants then categorized various challenges into different levels.

Commitment to creating this future

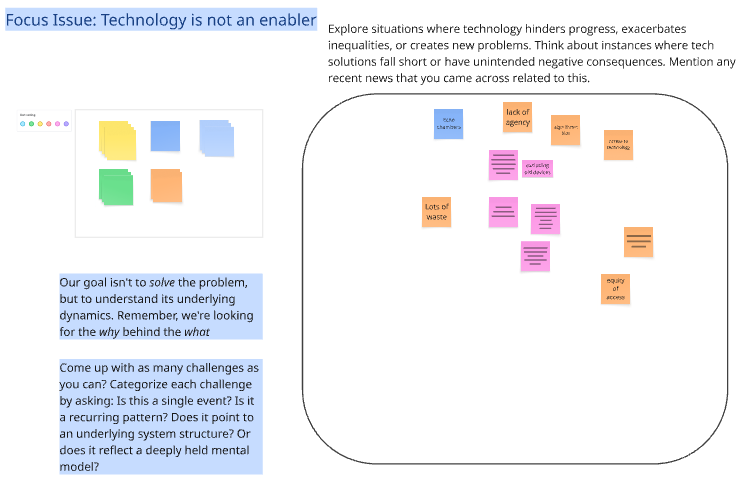

To bring this to life, we revisited a future scenario initially imagined during our first event: the promise of technology as an enabler. However, in this session, we acknowledged the current reality—that for many, technology is not an enabler.

We framed the challenge as: Explore situations where technology hinders progress, exacerbates inequalities, or creates new problems. Participants were encouraged to reflect on instances where tech solutions fall short or have unintended negative consequences, and to share any recent news stories that illustrated this dynamic.

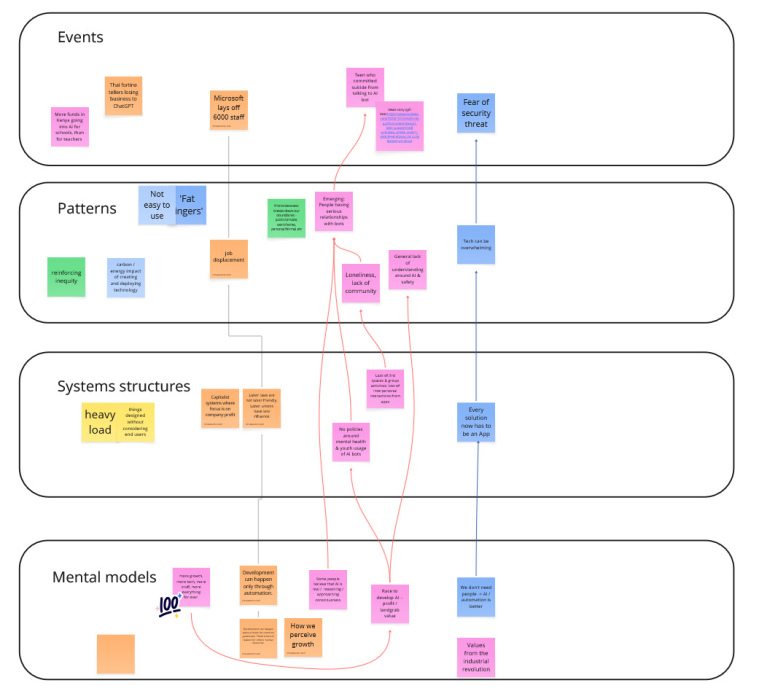

Our objective wasn’t to solve this complex issue during the workshop, but rather to deeply understand its underlying dynamics. Participants then collaboratively brainstormed a multitude of challenges, categorizing each one through the Iceberg Model: Is this a single event? A recurring pattern? A symptom of an underlying systemic structure? Or a reflection of deeply held mental models?

The results were revealing. Diverse icebergs emerged, showcasing events such as “More funds in Kenya going into AI for schools than for teachers”, “Thai fortune tellers losing business to ChatGPT”, “Microsoft lays off 6,000 staff”, “Teen dying by suicide after interacting with an AI bot”, and “Growing fear of security threats.”

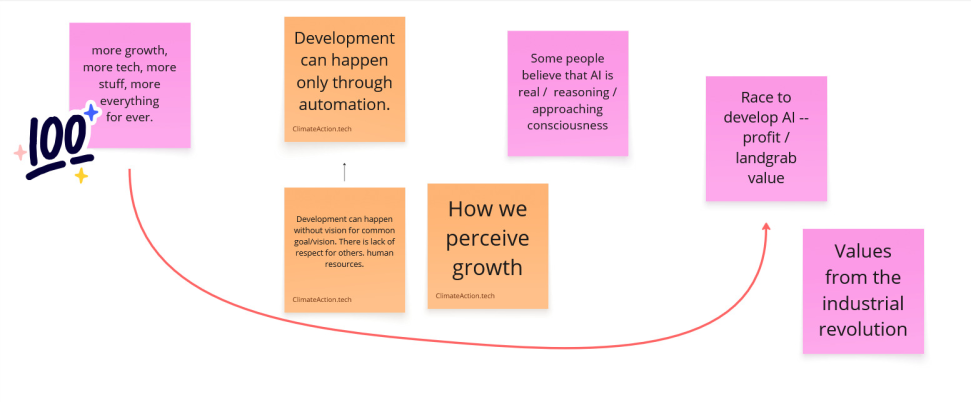

Remarkably, despite the variety of events, a strikingly consistent set of mental models surfaced, suggesting they all stemmed from a shared paradigm of thinking.

Systems Series 3: Designing fundamental solutions

Truly sustainable change requires addressing the underlying structures and beliefs that perpetuate unsustainable practices. By designing fundamental interventions, we can move beyond treating symptoms and create a resilient, equitable, and ecologically responsible tech ecosystem.

Our final 90-minute co-creation session will focus on this crucial step. Here’s what you can expect:

Revisit the systems map: We’ll briefly review the iceberg models that were created during the previous workshop, ensuring a shared understanding of events that are happening. We would look at a few archetypes of systems thinking such as limits to growth, fixes that backfire and tragedy of commons.

Explore systemic intervention strategies: We’ll introduce and discuss various approaches to systemic intervention, from shifting mental models and altering feedback loops, to redesigning core infrastructure and challenging underlying power dynamics.

Co-design fundamental interventions: We’ll be brainstorming potential interventions that address the root causes of unsustainable tech.

If you would like to participate in understanding the current reality with other CAT changemakers, you can register for the Systems Series 3 workshop happening on Thursday, June 19. If you can’t attend, you can keep contributing to the series by putting your thoughts on Miro and participate in discussions in the #systems-series CAT Slack community channel.

Let’s continue to map the current reality and design fundamental solutions using systems thinking.

Acknowledgements: A special thank you to Jon Sleeper for bringing his coaching experience to introduce us to the Cynefin framework, and making us understand the difference between complicated and complex systems. I would also like to express my sincere appreciation to Melissa Hsiung for her help with the series planning.

References:

The workshop is built using the following books

- Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows

- The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge

- Systems Thinking for Social Change by David Peter Stroh

I’m interested with the discussion.

The climate change and sustainable environment are the concern for all. I’m very interested to participate in this discussion.